|

|

In the introduction to his play ‘Jaques and His Master’ Milan Kundera writes the following:

“I often hear it said that the novel has exhausted all its possibilities. I have the contrary impression: during the four hundred years of its history, the novel has missed many possibilities; it has left opportunities unexploited, roads unexplored and calls unheard.”

It’s an intriguing thought, and one that doesn’t sit well with the conventional mindset that culture should always be evolving in some aggressively unique way. Contemporary music in particular still values the acquisition of new forms and compositional techniques (above the importance of content) even if it’s many years since anything genuinely ‘new’ came along.

For most composers the trajectory of their creative development is a linear one – an unbroken line connecting each work with the next – and I’ve experienced this myself, gradually modifying the way I write as new ideas and influences are assimilated. So I was surprised to find that when I came to composing tangos I could creatively vanish and immediately arrive somewhere else in a ‘Beam me up, Scotty’ fashion: materialisation within an alien musical language.

Tango arrived in my life by chance – the opportunity came to compose a new work for the London group Tango Volcano and I just jumped at it because like many classical musicians I’d fallen in love with the music of Piazzolla. At first I saw this as simply a fun and curious thing to do, without realising the musical possibilities it would open up. This first piece, Milonga Azure, has since been played in over twenty different instrumentations, from duo versions right up to an arrangement the BBC Concert Orchestra commissioned for a ‘Discovering Music’ programme on Radio 3 on the history of tango.

Alba, for violin and piano, was one of the tangos that followed soon after Milonga Azure. I’ve rarely written a piece so fast; the first two pages emerging virtually complete as quickly as I could scribble them down (by contrast, another work of the same period, Spanish Café, took several attempts, and four years, to reach its final shape!). The mood of Alba is one of melancholy and nostalgia; emotions that are central to tango. This backward glance – a re-imagining of the past – is something that has always been part of Western culture. It can be traced from Homer and Virgil, through to Picasso, Cocteau, Maillol, and many others. The intersection of different styles and periods blurs the boundaries of the artwork, producing a quality that transcends the differences of idiom, time, and place. Alba emerges from impressions of earlier violin repertoire, but seen through a 21st century lens; refracting its tonal and rhythmic constituents in ways that are unfamiliar. Alba has had many performances in recent years, mostly on violin, but on sax and flute as well, and current performers include Noah Getz in the US and Mifune Tsuji in the UK.

Tango has given me the chance to journey down some of those unexplored roads that Kundera writes about - looking forwards, but also backwards.

The woodcut illustration for this post is by Aristide Maillol.

0 comments

Last year I spent a couple of days at the Leeds Conductor’s Competition: Britain’s leading competition of this type, which happens every 2-3 years. I was there because an orchestral work of mine was being used as the modern test piece at a stage in the event in which there were only six contestants left. Each competitor had a slot to rehearse some Stravinsky, Rachmaninov, and my own piece. It was a fascinating experience on so many levels, not least in that it gave me the opportunity to hear my own music interpreted by six different conductors! Last year I spent a couple of days at the Leeds Conductor’s Competition: Britain’s leading competition of this type, which happens every 2-3 years. I was there because an orchestral work of mine was being used as the modern test piece at a stage in the event in which there were only six contestants left. Each competitor had a slot to rehearse some Stravinsky, Rachmaninov, and my own piece. It was a fascinating experience on so many levels, not least in that it gave me the opportunity to hear my own music interpreted by six different conductors!

Since then I’ve spent some time musing over the nature of competitions, and come to the conclusion that there are basically three main types;

1) The Dead Certain. This is the sort of competition you get in sport; clear winners, and losers. Whoever runs faster than everyone else/jumps higher/scores more points or goals.

2) The Somewhat Hazy. Here the framework of winning and losing is more complex. I’d put arts based competitions in this category; the Turner Prize, Booker Prize, the Leeds Piano Competition (as well as the conducting one), and so on. Within this context a panel of judges may well take differing views on the quality of the artistic creations they have to appraise, and how to rank them, but they still have access to what they asses; they can read books, see works of art, and listen to performances.

3) The Downright Dubious. There’s only one candidate for this category; composition competitions. Here’s a typical scenario - one hundred and fifty composers submit orchestral works which are up to 20 minutes long, they are scrutinised by a panel, and the winning composition gets a cash prize and performance. At no point in this process do the judges get to hear the pieces in question! Given this situation one wonders how on earth it is possible to make a critical assessment of as much as fifty hours of dense and difficult music without even hearing a note performed (and forget midi playbacks, they’re a waste of time for orchestral works, and everything else really).

Instead of these random lucky-dip composition competitions wouldn’t it be wonderful for composers (especially younger ones) if every orchestra was to set aside a couple of sessions a year in which they’d read through and record previously unperformed orchestral works. Not an ‘open to the public’ workshop (these often seem to waste time with meaningless discussions that involve the audience), but simply a chance for a composer to hear his or her piece, get feedback from the orchestra, and take home a good quality recording.

No prizes, winners or losers: just a chance for composers to listen and learn in a sympathetic environment. I know that this is a crazy idea, given the scarcity of rehearsal time for most orchestras, but it’s a nice thought.

8 comments

(With apologies to Jim Aitchison, as this covers some of the same ground as his own recent blog) (With apologies to Jim Aitchison, as this covers some of the same ground as his own recent blog)

How very ‘present’ the past is these days. Our daily existence finds the past ghosting up beside us and making an appearance in so many ways: retro designs, the nostalgic costume dramas and history programmes on TV, and the current fascination for tracing the family tree, to name a few of many examples. No other culture has been as entranced with previous times as our own is.

I find the past endlessly fascinating, not for the reasons I’ve mentioned above but for the fact that it gives us a chance to see the world through other’s eyes, to try and break out of our own contemporary conditioning. When I’m in London I’ll often visit the British Museum, and wandering from room to room I come across affirmations of being and awareness; the way octopus designs curl cleverly around Minoan pottery, the Sumerian sculptures of power and shamanistic presence, the perfected and dramatic forms of ancient Greece. As I can’t access the music of these distant cultures I can at least see how they created artefacts that tackled problems of visual depiction - form and space, the precision of content – and somehow this experience, and my reflections on it, throws my own creative processes into relief. It also shows me how much creativity is enabled, and restricted, by the medium that is available for it to work through.

From a musical point of view, a quick survey of the contemporary composer’s resources proves illuminating. Instruments have reached a stage of ‘finite technology’; there are only so many ways one can produce sound – blow, pluck, scrape - and these seem to have been mostly explored. Electronic music has added a new dimension, but has failed to have more than a fringe impact in the classical arena. Another piece of finite technology is tonality, which slowly developed its complex and expressive system of harmonic relationships until it appeared to exhaust all possibilities. As classical composers we worry a great deal about the regressive aspects of writing tonal music, but the rest of the musical world seems happily undisturbed by this question – pop, rock, jazz, and many other styles, continue to produce new music that recycles the same harmonies. Are we fretting unnecessarily? After all, novelists fashion their work within the context of a verbal language that is developing very slowly, and mostly by small additions of vocabulary than by any larger changes to grammar and syntax.

If instruments are no longer developing in new directions, and if it is hard to create any previously unused harmonic relationships, is there any sense of the ‘new’ in music. Is it even necessary? Am I running up a white flag by suggesting that novelty and innovation are no longer a composer’s prized aspirations?!

Much of the music written in the decades that followed 1945 had something of the ‘shock of the new’ about it; graphic notation, improvisation, total serialism, silence, mobile forms, and so on. Many of these innovations have withered and failed to produce a genuinely new language that can move music forward; there were of course interesting offshoots from these experiments that shouldn’t be ignored, but they have not become mainstream. More importantly, there was a mindset during this period that contemporary music should be intensely serious, profound, difficult (to both listen to, and perform), and always striving to break new ground. This approach seems to have alienated audiences to the extent that contemporary classical music is now virtually off the cultural map.

François Couperin once wrote, ‘I would say, quite honestly, that I greatly prefer that which touches me to that which surprises me,’ a viewpoint that I’d concur with. The question of what was being communicated in post war music was at times ignored in favour of a scramble for innovation; no wonder so many listeners lost interest. Technical modifications and cutting edge processes were rarely partners to new sentiments, although some composers could do both, and continue to excite me today as much as they did when I first encountered their music.

This is why, for me, the experience of hanging around the British Museum is so important – a mixture of caffeine and culture is always heady anyway. Looking at the exhibits one can see objects that offer up passion, beauty, ritual, enjoyment, pleasure, craftsmanship, and many other qualities. Some show incredible technical refinement, others have a strange mythic presence.

The creative hurly-burly of the last two centuries (or to be precise, the whole process of the emancipation of the artist after the French Revolution) seems to have slowed. If we are to get modern classical music back into cultural life perhaps we need to worry less about the future of music, and more about the qualities we invest in the pieces we are writing right now. Those who fashioned Greek vases, or the decorative motifs of ancient Egypt, were not concerned with ground breaking innovation, but with pleasure, meaning and communication, which is why these objects still speak to us after all this time.

An afterthought: I was listening to BBC Radio 4 today – there was a trailer for a new series of programmes in which the comedian/writer/actor Lenny Henry is to explore three things that he’s always failed to get his head around. The trailer announced, ‘Lenny Henry will examine the plays of Samuel Beckett, the paintings of Jackson Pollock…and maths.’ There was a slight pause before the ‘and maths’ bit, in which my mind automatically filled in the blank with ‘the music of Stockhausen’. It was a logical thought, literature/art/music; but it turned out to be one of the many instances in cultural life that one notices contemporary classical music only because of its absence!

6 comments

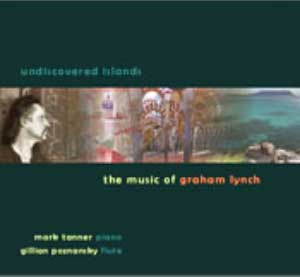

I always think that it’s interesting how others see one’s music, compared to how one views it oneself. This has been brought home to me a bit by recent reviews of a CD of mine, Undiscovered Islands; piano works, plus a few flute pieces. I should say (if you’ll forgive me!) that the reviews have been hugely positive and constructive, but they have also made some interesting observations. Amongst the comments a number of reviewers have referred to my music as being ‘tonal’ – for example, in International Record Review, “Lynch's interest in non-European music and cultures, and in both reality and imagination, serves his music well, demonstrating that tonality has yet to be exhausted.”

Me, tonal? It hadn’t crossed my mind (apart from the tango nuevo pieces that I write). I don’t use key signatures, don’t think in keys, there are no conscious modulations, and I rarely use triads – so where’s the tonality?! Yet, I can see why the reviewer would say this, and I guess we all probably have a personal definition of what we hear as ‘tonality’ anyway.

If I can just backpedal for a moment to when I was at university doing postgraduate composition in the 1980s/90s, in those days pretty much everyone wrote atonal music; it seemed the only ‘serious’ musical language one could use. But I recall buying a copy of the original two piano version of Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite in a second-hand book shop, and being totally knocked out by what I discovered: perhaps an odd choice of piece to zap myself with amongst all the Stockhausen, Ligeti, and Birtwistle that I was listening to. I’d known the orchestral version of Ravel’s work from when I was younger, and many other pieces of his, but what struck me about playing it on the piano was the incredible simplicity and stunning accuracy of the harmonies, the way each chord sounded as beautiful and vivid as it did in the orchestral version; perhaps better, in a curious way.

Ravel was of course a scrupulous and detailed composer, choosing every harmony with care and bringing each chord to life within the context of its surroundings. The harmonies feel as fresh as colours in a Matisse cut out, and whilst there is a linear harmonic functionality Ravel’s chords often stand out like objects in a landscape; complete and self contained sculptures. This was quite an influence on me, along with the tonality bending qualities of some of Debussy’s last works.

As a student there was a time when I felt that any harmonic choice existed solely between tonality and atonality: a sort of inescapable Scylla and Charybdis lying in wait. Now I feel that there is a ‘post tonal’ music out there that many composers are tapping in to, one that treats consonance as an individual sonic moment, rather than as a fragment in an obsessive functional scheme. An example might Unsuk Chin, whose violin concerto shows the influence of later Ligeti in the way its often attractive harmonies unfold, and are counterpointed against passages of complex dissonance. The use of consonance allows for contrast, and consequently richer structural possibilities.

So, is tonality dead or alive? I don’t know. But I do notice that consonant harmony has made more of a return, but within a pacing and context that is clearly 21st century. A friend who is a long standing member of the BBC Symphony Orchestra also confirmed this in a conversation we had the other day, she’d noticed the gradual change. Maybe ‘post tonality’ is a bit like getting older - we’re all slowly doing it, but, like me, without really noticing!

0 comments

|

Concert Listings Today & Tomorrow:

|